Dabbahu Magmatic Segment

Dabbahu Magmatic Segment

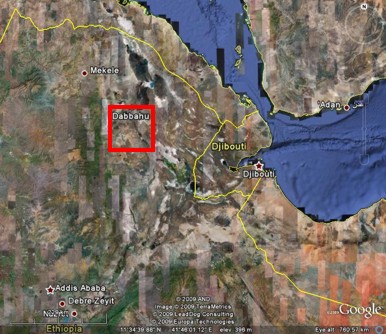

The Dabbahu magmatic segment is about 60km long and 15km wide. At the northern end of the segment are the major silicic strato-volcano Dabbahu and the smaller Gab’ho volcano and in the south is the Ado’Ale silicic central volcanic complex (Rowland et al, 2007). Figure 5 shows a series of Google Earth images of the Dabbahu magmatic segment and the dyking event in September 2005.

Dabbahu volcano is 1350m above sea level and about 10km diameter. To the northwest is a linear vent zone with smaller volcanoes and cinder cones (photo 1) and to the south is a well developed axial graben which decreases in size towards Ado’Ale. The Ado’Ale volcanic complex covers a wide area of the central Dabbahu magmatic segment and is over 750m above sea level. To the south of Ado’Ale the elevation of the rift zone drops beneath the regional level (Rowland et al, 2007).

The Dabbahu magmatic segment is about 2000km2 in area and 1200 distinct faults/faulted fissures have been mapped across it using satellite data (Hayward, 1997).

In the north of the segment faults strike close to north-south, oblique to the extension direction. To the south of Ado’Ale faults strike closer to northwest-southeast and perpendicular to the extension direction (Rowland et al, 2007). The mean length of faults is 1.9km, with linkage between fault segments forming en echelon fault zones up to 20km in length. Whilst most faults are down-thrown towards the axial graben, facing varies across the rift zone and grabens are found on the segment flanks. Within the 7km area of the rift axis, the faults and fissures are closely spaced, less than 500m apart and cover the same area as the youngest basaltic lava flows. The faults are close to vertical at the surface having formed by the opening up of pre-existing cooling joints. They show no evidence of frictional contact along the fault planes and have throws up to 20m and opening displacements of 1-3m. Deep cracks occur between footwalls and hangingwalls and in some cases have been used by mafic magmas as channels to the surface. Although the faults are near vertical at the surface they are less steep at depth as show by the development of monoclines in the strata within the fault hanging walls (photo 2). The footwalls are generally undeformed (Rowland et al, 2007).

Field observations of structures associated with the seismic event in September 2005 correlate with the distribution of recorded seismicity and are consistent with the intrusion of a dyke to depths greater than 2.5km. If the September 2005 is a typical rifting event with typical fault growth then the minimum number of such events needed to account for the current rift geomorphology can be estimated. This is about 400 rifting events which together with the time average opening rate of 16mmyr-1 gives a minimum of about 200 thousand years for the topography of the rift segment to develop. It demonstrates that rift valley topography can develop by dyke intrusion alone and that alternating phases of magmatism and tectonism are not needed to account for the topography (Rowland et al, 2007).

Top:

Volcanic cones near Barantu, NW of Dabbahu volcano. (Photo: Tim Wright,

University of Leeds). Right: The light coloured sediment on the fault

surface is sediment that has not yet been weathered away by the wind and

so acts as a way of assessing the relative age of surface features. The

aeolian sediment has settled in cracks in the ground, usually cooling

joints within basalt. When these joints are uplifted during faulting the

pale sediment is exposed. Over time it will be weathered away by the same

katabatic winds from the highlands that deposited it, leaving the dark

coloured, older fault scarp (Rowland et al, 2007). Photo by Julie Rowland,

University of Auckland.

Top:

Volcanic cones near Barantu, NW of Dabbahu volcano. (Photo: Tim Wright,

University of Leeds). Right: The light coloured sediment on the fault

surface is sediment that has not yet been weathered away by the wind and

so acts as a way of assessing the relative age of surface features. The

aeolian sediment has settled in cracks in the ground, usually cooling

joints within basalt. When these joints are uplifted during faulting the

pale sediment is exposed. Over time it will be weathered away by the same

katabatic winds from the highlands that deposited it, leaving the dark

coloured, older fault scarp (Rowland et al, 2007). Photo by Julie Rowland,

University of Auckland.

Click here for more information on the recent volcanic activity in the Dabbahu area.

Structural Geology of the Afar Region